I am supposed to be curating my color slide collection so I can make thousands of digital copies that no one will ever see. I got distracted because I had to find my old slide sorting light tables and in the process also found a box with three old cameras. Two of these might have been in the family since the 1930s and the other was acquired more recently, although it is the oldest of the three.

The youngest camera is my mother’s Kodak Brownie No. 2 Rainbow Hawk-Eye Model C Box Camera (Figure 1). This was made of cardboard and is probably the 1930 reissue of a rather primitive 1913 model. It sold for a dollar or two and Kodak gave away hundreds of thousands of them to kids (Kodak’s plan was to make money on film and processing). It is little more than a pin hole camera. It has a lens (one element), but it does not focus. It has a shutter, but only one shutter speed (about 1/25th second). It has only one aperture (f/11). So to get the correct focus and exposure you had to choose a subject the right distance away and the correct brightness. Then there was one button to push. It was as easy to take photos as it is today if you only wanted to take photos of things 8 feet away that were not moving and under a bright sky.

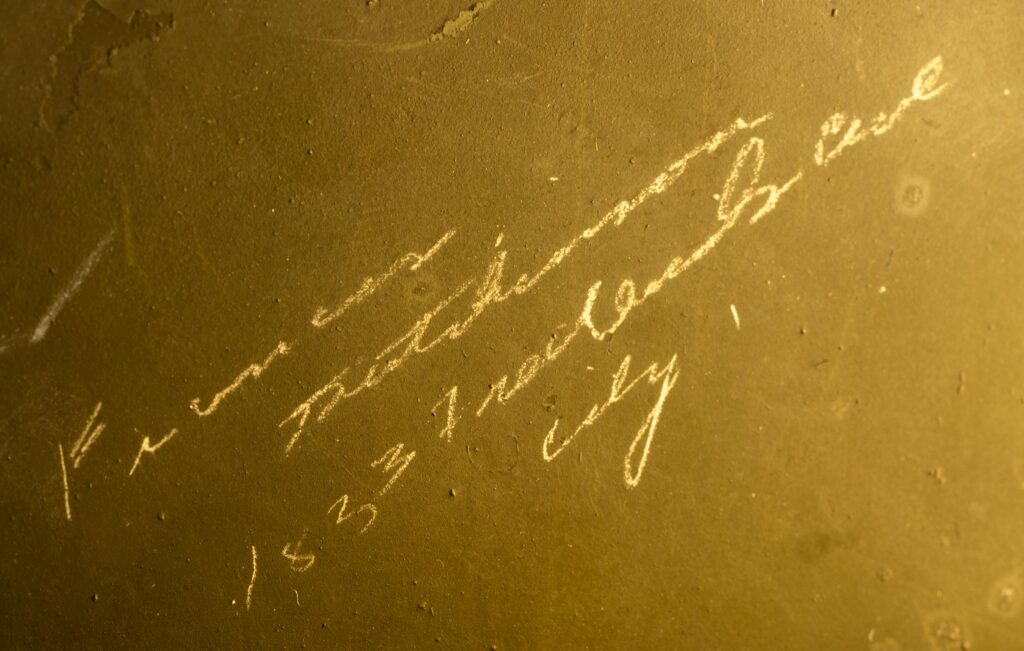

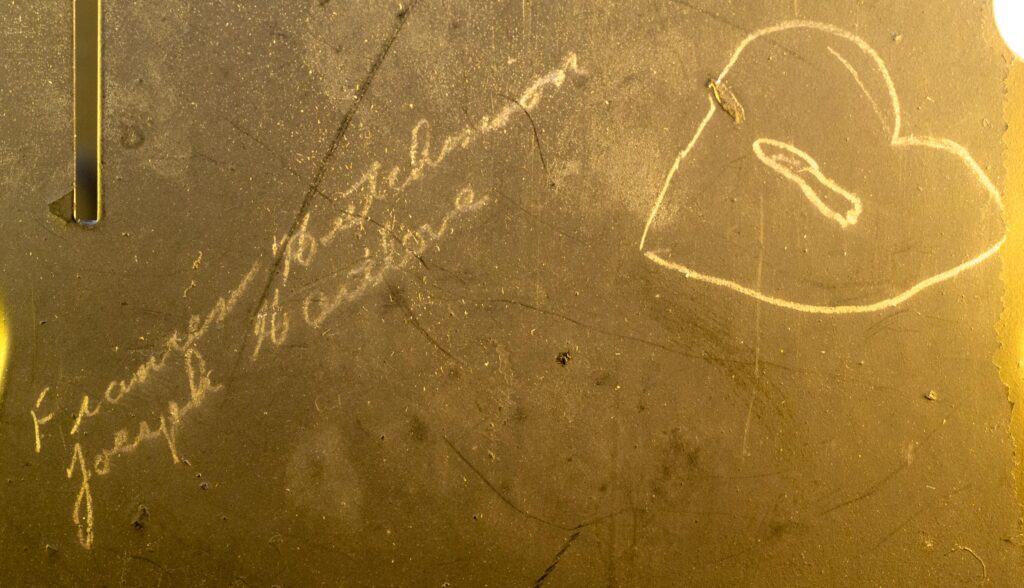

My brother thought this was my mother’s camera, and it was easy to learn that he was right. Inside the camera is a black sheet-metal structure for holding the 120 film. My mother had distinctive handwriting which is all over the black metal (Figure 2). She wrote her name and address, a date, and the name of what I suspect is a fantasy boyfriend.

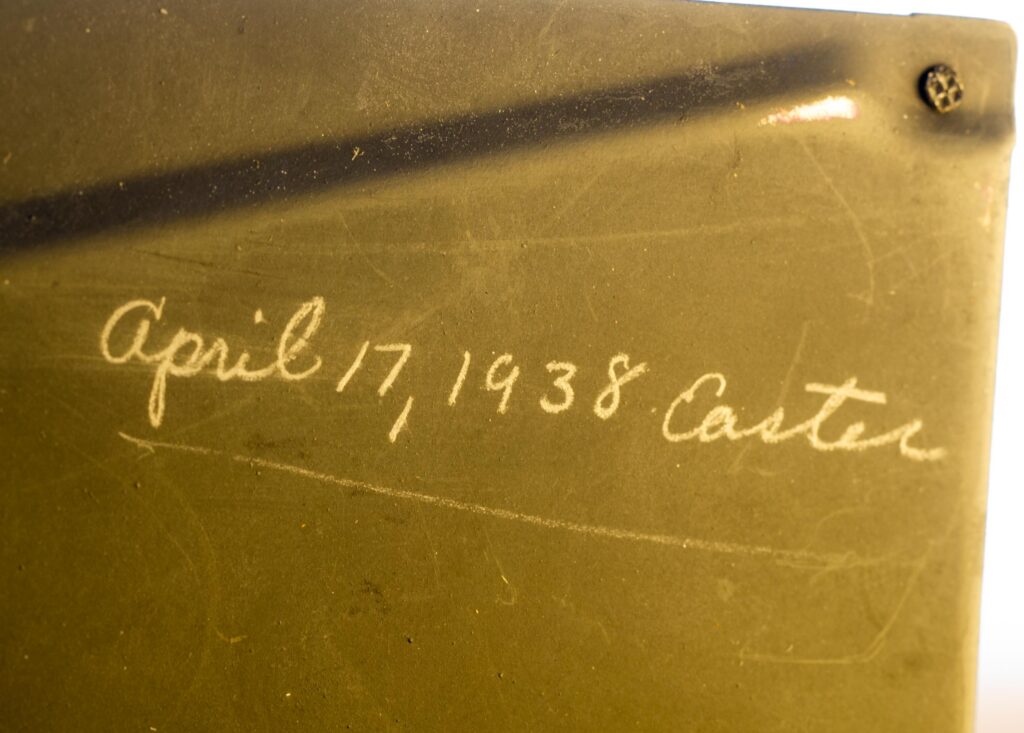

This camera was apparently acquired by my mother on or before on April 17, 1938 (Figure 3). This model was probably still being sold then. On that date my mother was only 15, and that is why I suspect that “Joseph Hartlove” (Figure 4) was a figment of her imagination. But maybe high school in 1938 was not how I imagine it.

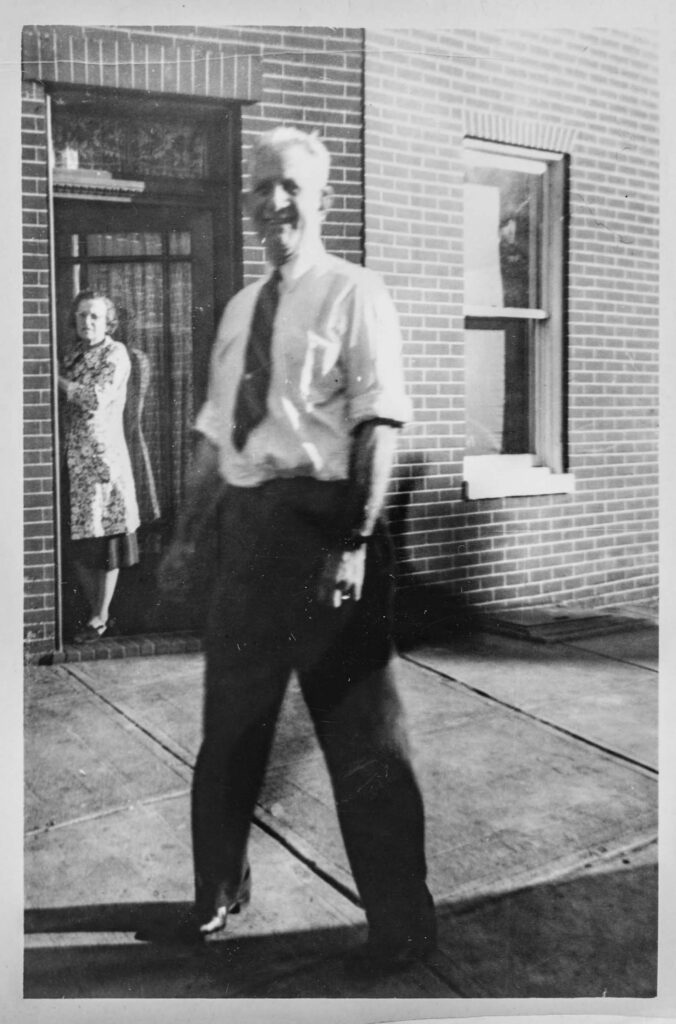

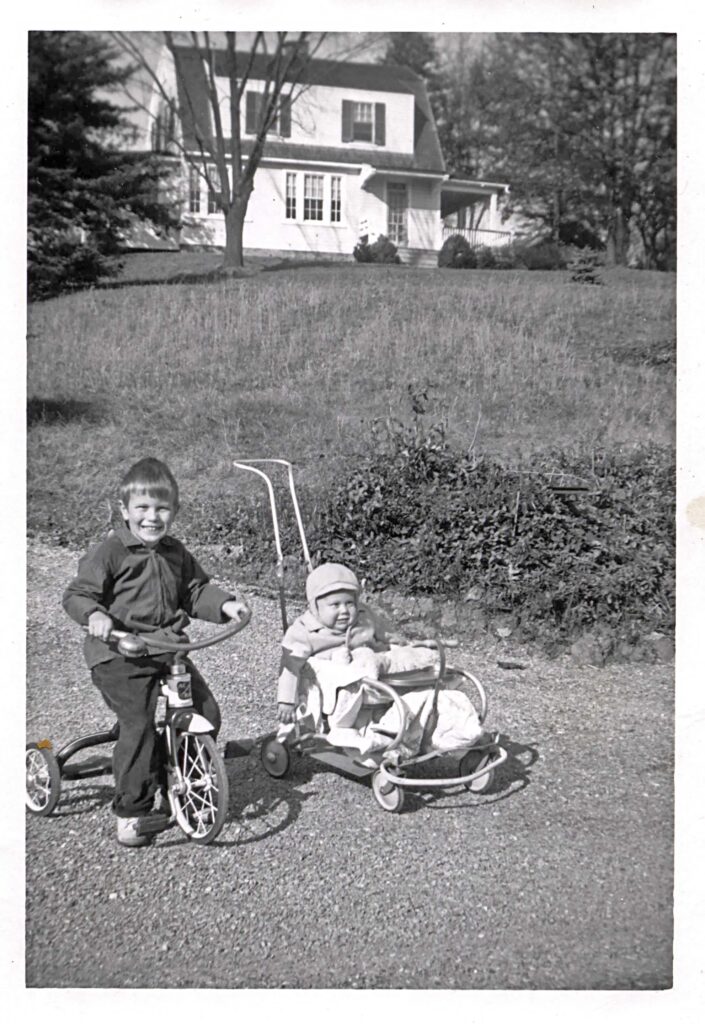

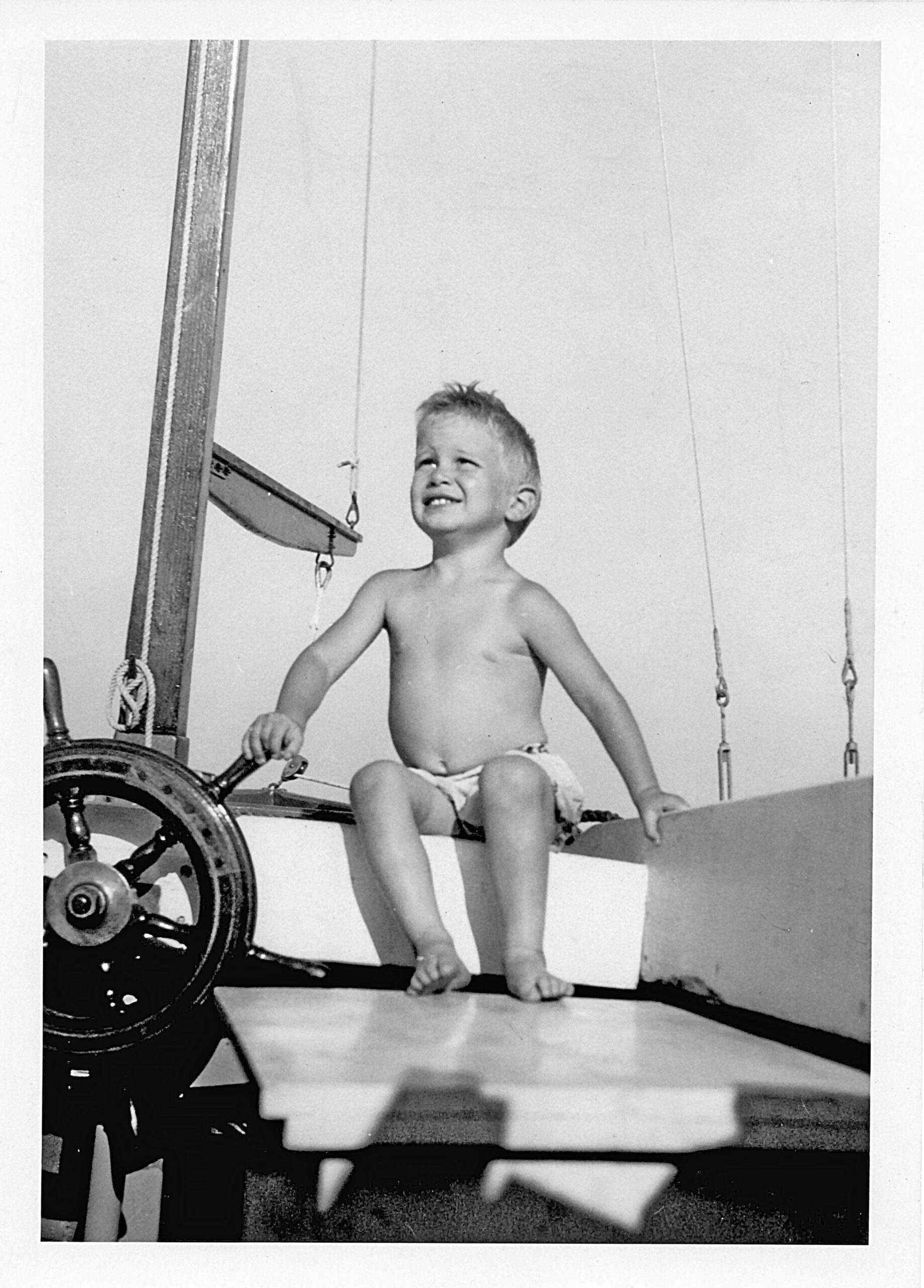

There are a few photos in the family collection that are probably taken with this camera (Figures 5 and 6). Photos from this camera are not crisp. Everything farther than about 6 feet from the camera is in focus, but not very sharp. The recorded scene is typically brightly lit, but not too bright — full sunlight led to overexposure and those washed-out photos were not prized so most have not survived. The photos are usually in portrait mode because the only viewfinder on the camera made it difficult to take photos in landscape mode. To use the viewfinder you looked down from above the camera, so the camera was held at chest or belly level, not eye level.

The next older camera is a No. 1 Autographic Kodak Special Model B Folding Camera (Figure 7). This model was manufactured between 1921 and 1926 and this one has a patent date of 1922. I assume this was my father’s camera but he was only 10 in 1926 so he probably acquired it second hand much later. The camera is well worn — not from abuse but from lots of normal use.

The Special Model B was an unusually well made and technologically advanced camera for Kodak and cost $50 in 1924 ($870 today) . The body is aluminum and covered with sealskin. The lens has four elements. You can focus it and select an aperture and shutter speed. The lens can be tilted to focus simultaneously on closer things at the bottom of the image and farther things at the top of the image. This was a professional camera.

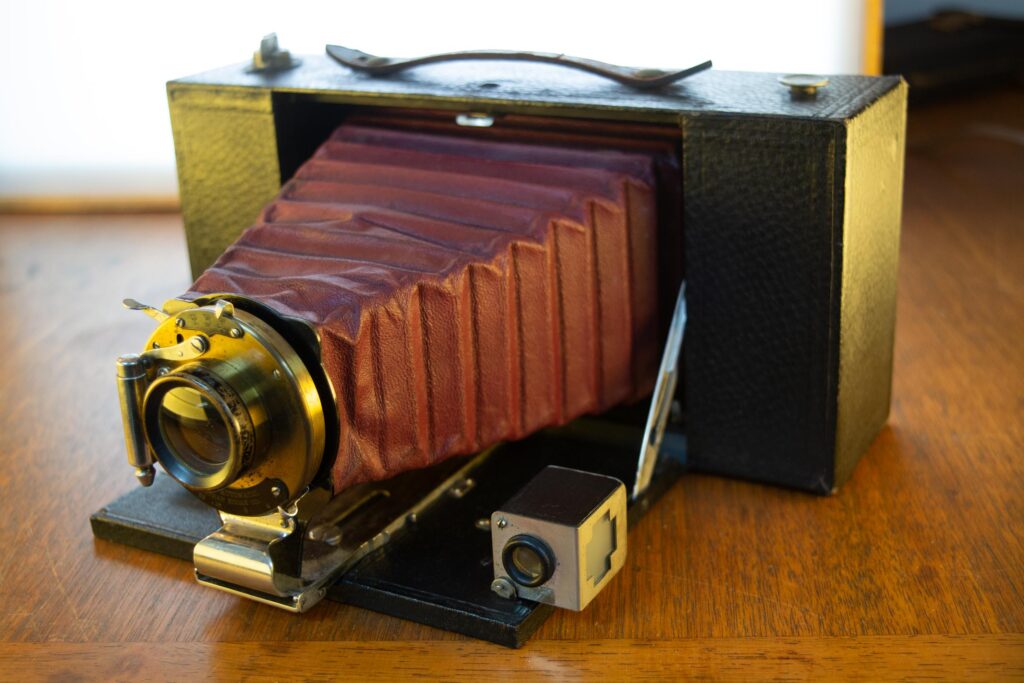

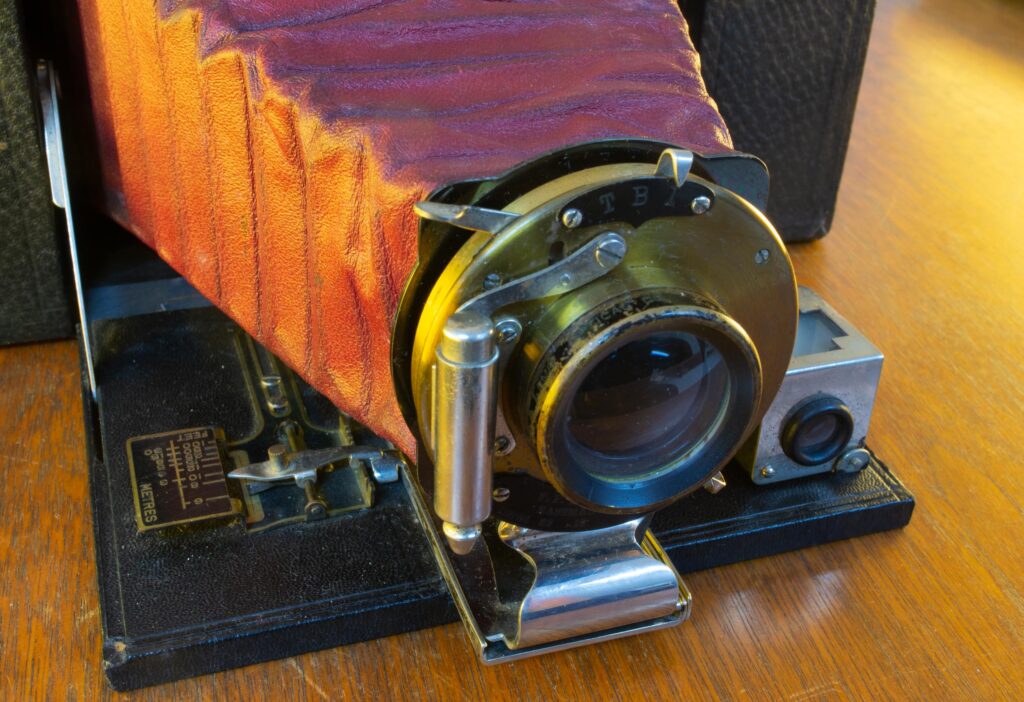

The oldest camera in the family collection is not really a family camera but one bought at a rummage sale in the 1960s by my brother. It is a Kodak No 3A Folding Brownie Camera Model A made between 1909 and 1915 (Figure 14). It was an inexpensive camera made of wood covered with fake leather. It has a single element lens and a single shutter speed (plus Bulb and Time). You could adjust the focus and select an aperture. It has handsome maroon leather bellows which date the camera to before 1913.

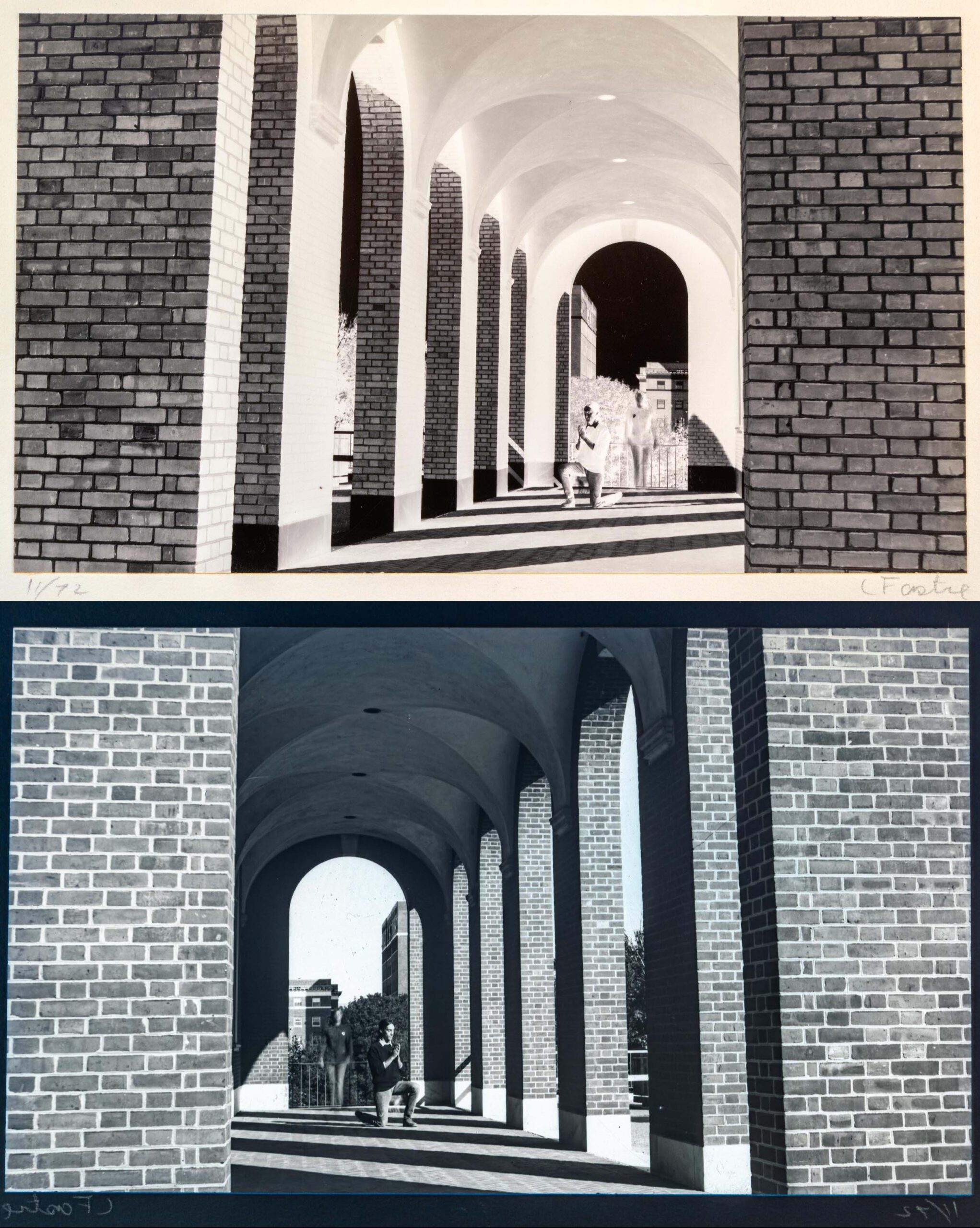

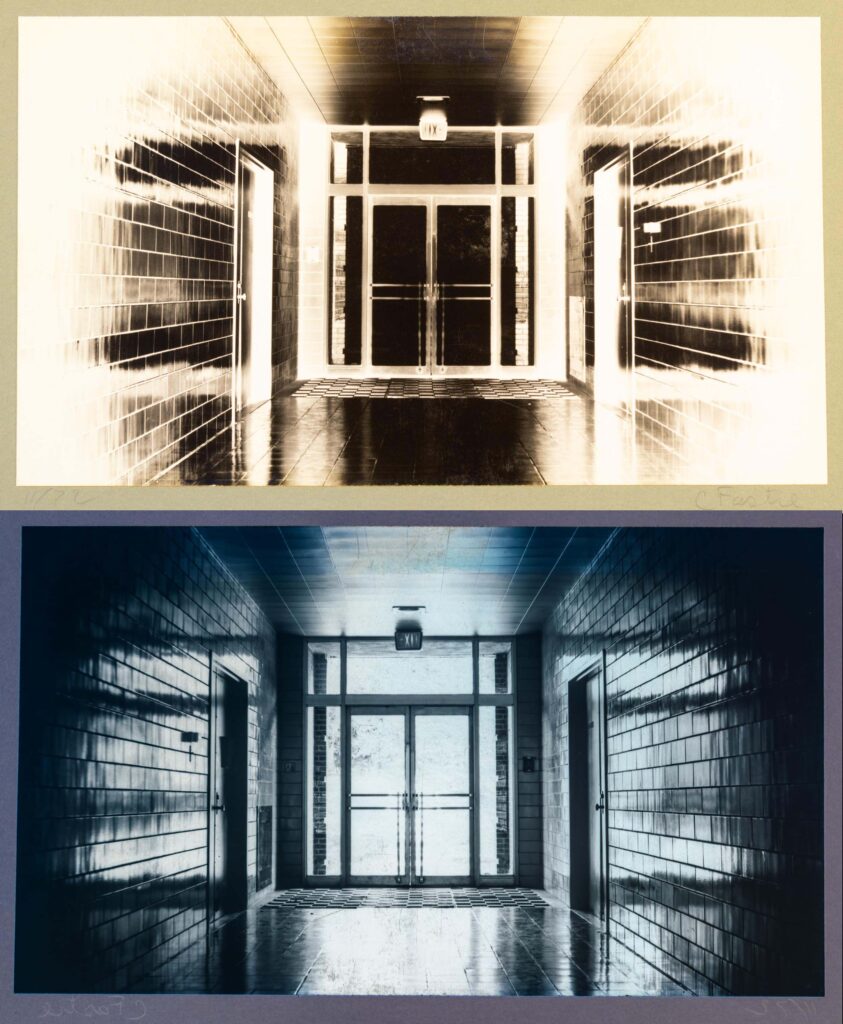

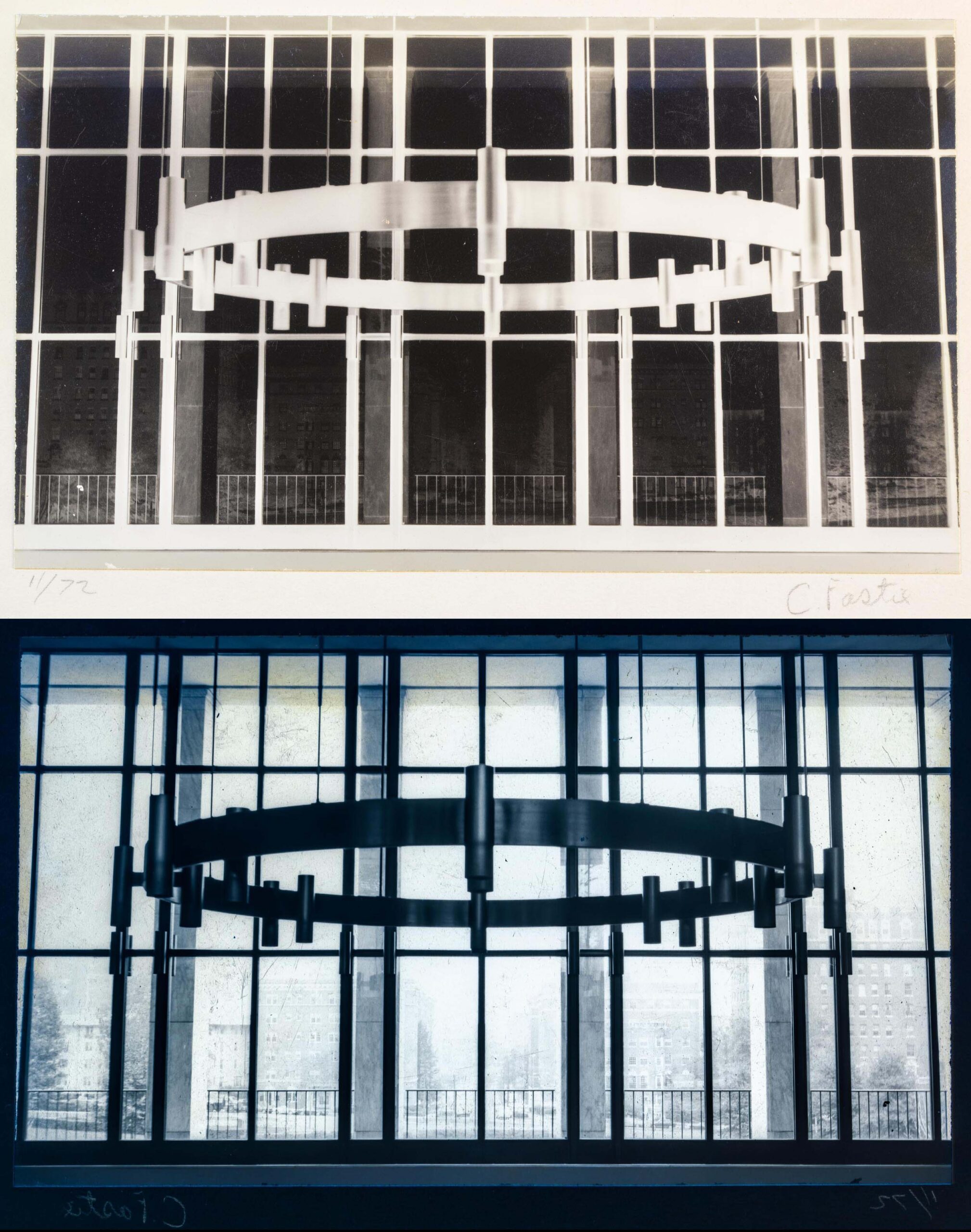

This camera was not used by my ancestors a century ago, and my brother never used it. But 50 years ago during my senior year of college, I did. Kodak stopped making the huge 122 roll film for it in 1971 so I put single sheets of photographic paper where the film should be. I then walked around looking for a subject, took a single photo, then found a dark place to open up the camera and replace the paper. I developed the paper in a darkroom like normal prints. Of course these were negative images.

I made about a dozen prints with the camera. These little curio negative prints were never intended to be turned into positives. But that’s easy to do now in Photoshop and I was curious to see what they looked like.

None of these cameras is worth more than $100 today. My mother’s box camera, which sold for a couple of dollars in 1930, is now worth $20-$60 and so are the two older cameras that sold for 1o or 20 times more. It’s a little surprising that the cameras have so little value today considering how many web sites and blogs are devoted to describing every detail of them and even displaying new photos taken by them (guilty as charged).

I think I won’t put these cameras back in their box. I will leave them out where I can watch them get dusty and they can continue to conjure images of other times.

This is completely inspirational to me. The entire journey of your collection of cameras from family members, developing films and the trip down memory lane has inspired me. I like the old photos and the lack of detail in the photos leaves us with a sense of mystery the unknown; something to think about an wonder.

Fascinating stuff. Who would have dreamed that, one day, you would begin a sentence with “50 years ago during my senior year of college…”.

Who would have dreamed that, one day, I would begin another sentence with “70 years ago my mother took two photos from the same place with no concept that 70 years later someone in the photos would digitally combine them to reveal the entire front yard of his childhood home.”