Indiana bats live throughout the US Midwest and into New England. In winter they gather in a small number of caves where as many as 50,000 bats may hibernate together. This makes the population vulnerable to vandalism and since 1967 the Indiana bat has been on the US endangered species list. It was listed as Vermont’s first endangered species in 1972. Communal hibernation also makes bats vulnerable to the spread of white-nose syndrome and Indiana bat populations have declined moderately since the disease appeared in 2006.

Vermont is at the northeastern edge of the Indiana bat’s range where it has been observed foraging and raising young throughout the southern Champlain Valley. About 10 maternity roosting colonies where females raise their pups have been documented in Addison County. Female bats select forested sites with large trees and spend the day under loose bark with their single pups and forage at night for flying insects within two or three miles of the roosting trees.

I have listened for bat calls at night using a gadget for my phone which captures the ultrasonic calls and transforms them into lower frequency sounds I can hear. The phone app also attempts to identify the species of bat calling (Figure 2). Some bat species including big brown bats, silver-haired bats, and little brown bats can be heard almost everywhere on summer nights in Addison County. Very occasionally the phone identifies a call as an Indiana bat. The calls of the Indiana and little brown bat are similar, so I was never certain whether the few Indiana bat calls are in fact mis-identified little brown bats. Maternity roosting offered a way to test the app.

On an August evening I visited one of Addison County’s southernmost known maternity roosting colonies of the Indiana bat. I had only a general idea where it was supposed to be, so I was looking for big trees and trees with loose bark, and I was also using the phone to listen for bats. I hoped to deploy two AudioMoths where Indiana bats were active to record bat calls through the night. The AudioMoths were set to start recording at 7:15 PM so when it was time I tied them to trees in areas that looked promising even though I had not heard any bat calls or seen any perfect looking roosting trees. I kept exploring and at 7:28 PM near some huge sugar maples I heard the first bat call of the evening. The phone app identified it as an Indiana bat and in the next 10 minutes identified 13 Indiana bat calls (e.g., Figure 3), more than it had in the year I have owned it. No other species were identified. I assumed I had not only found the roosting colony but demonstrated that the app could indeed distinguish Indiana bats from little brown bats.

I left the AudioMoths where they were and returned two days later to move them closer to the newly discovered bat hot spot (Figure 4). I listened again for bats with the phone app and heard more Indiana bats but this time also heard lots of big brown bats and a couple of little brown bats. Unlike the phone app, the AudioMoths do not identify bat species, so when using AudioMoth data I cannot reliably discriminate between Indiana bats and little brown bats which have similar calls. Big brown bats and silver-haired bats are also difficult to tell apart, but are easy to distinguish from Indiana or little brown bats.

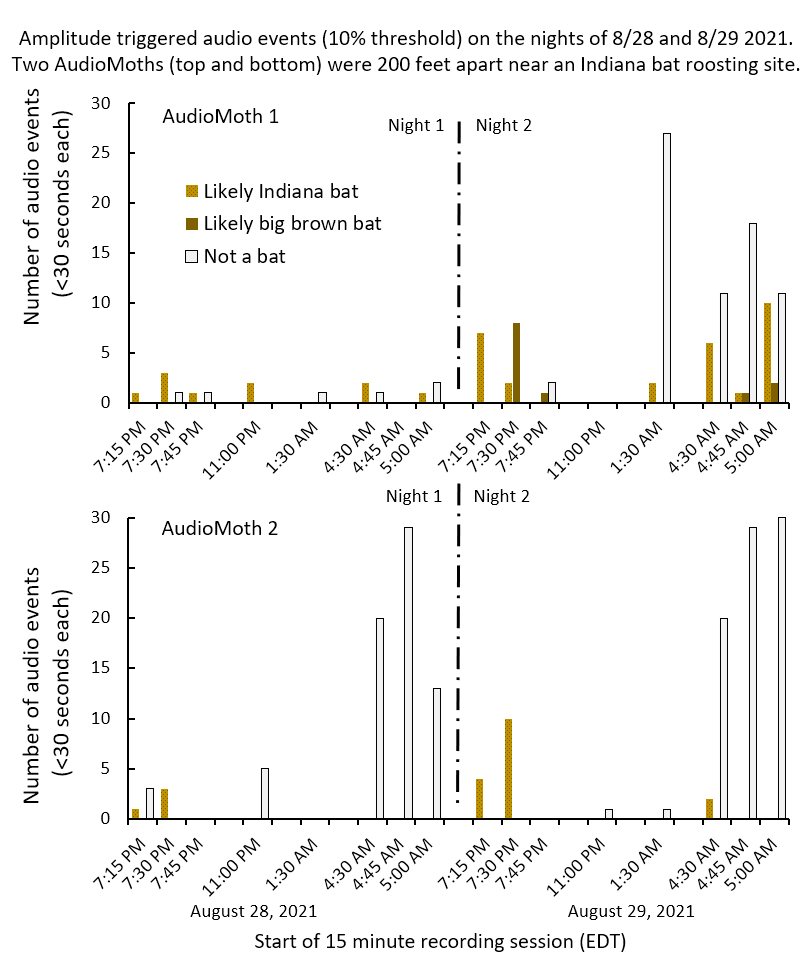

At the first recording site bat calls triggered less than half of the recordings (Figure 5, gray bars are recordings triggered by wind, rain, other animals, nearby human activity, or other bumps in the night). The substantial differences between the two nights and between the two AudioMoths, which were only 200 feet apart, suggest that many more nights of recording at many different places in this area would be required to learn much about these bats. I tried to design this recording effort to capture Indiana bats leaving the daytime roosting site at dusk to forage for insects, and then returning at dawn to the roosting trees. There is some indication of that pattern, but it is quite weak in these data. After moving the AudioMoths to the new location, they recorded for 10 nights before I retrieved them (Figure 6).

Although the new locations of the two AudioMoths were only 150 feet apart, each AudioMoth appears to have recorded different bats (Figure 6). The AudioMoth in a low area seems to have recorded lots of Indiana bats and the AudioMoth on top of a rocky ridge recorded mostly big brown bats. This could be because big brown bats were flying through the upper forest canopy (I watched them do this) and Indiana bats were flying lower (I did not observe them doing this). The AudioMoth on the high point might have been within audio range of the forest canopy while the lower AudioMoth was not. The lower site definitely seems to have had substantially more Indiana bat activity.

Sorting the results by time of night could reveal whether bats were leaving the roosting site at dusk and returning at dawn (Figure 7). There is some weak support for this, but if there is such a “rush hour” my pre-programmed recording sessions might have mostly missed it. A stronger pattern in these results is that there was less bat activity at 2:00 AM (“Early morning”) than at other times. And also that there is a lot of variability in what bats do.

For the 10 day recording effort I changed the amplitude threshold from 10% to 8% so quieter sounds would trigger a recording. This was a good threshold for this deployment and there were few non-bat recordings on most days (Figure 8). On the nights of September 5 and September 8 there were several dozen false triggers at both AudioMoth locations. These were due to rain which was heavy on those nights and resulted in near-continuous recording for some sessions (and lots of extra files to examine).

As is often the case, this exercise taught me more about how to use an electronic gadget than it did about biology. But it is good to be reminded that the endangered Indiana bat is carrying out its complex family life in healthy forest patches scattered among our houses and farms. Those forests are not just trees.

You can download the AudioMoth configuration file I used in both AudioMoths here.