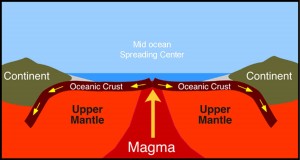

Below is a diagram that was never shown to me in science class. Alfred Wegener proposed his theory of continental drift in 1912, but it was not until 1960 that most scientists began to accept the new paradigm that continents move around. The idea of crust formation at mid ocean ridges came even later in 1966. So when scientists and teachers in the 1950s and 1960s presented a story about the serpentine rock underlying Soldiers Delight, they got it wrong. Serpentinite is formed in the lower oceanic crust, typically at the mid ocean spreading centers. That’s where it picks up its heavy minerals, like chromium, nickel, and magnesium, which are more abundant in the mantle and deep crust. When Africa floated over here 300 million years ago, a little bit of this oceanic rock got pushed along with it and ended up in the Appalachian Mountains, and in Soldiers Delight. Nobody knew that in 1960.

In a 1960 Baltimore Sun article, the Soldiers Delight bedrock is described as “volcanic, remains of a crater that simmered lava millions of years ago.” In 1965, a brochure printed by Soldiers Delight Conservation Incorporated repeated that it was “a thick layer of volcanic rock, the remains of a crater, active millions of years ago.” Like these quotes, the discussions about geology at Soldiers Delight when I was a kid were brief and vapid. No one knew much. No one could put serpentinite in its true context, which was not yet part of science.

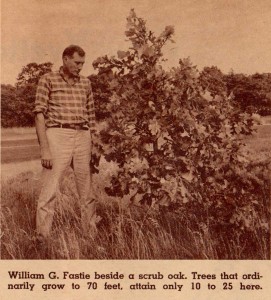

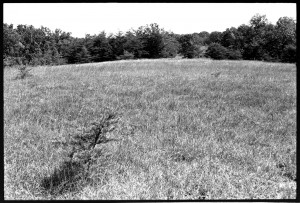

So my elders are forgiven for their geological ignorance. But that 1960 Sunday Sun article also includes two photos of smart people standing next to tiny trees in Soldiers Delight. Unlike the absent geology discussions, everybody talked about how the unusual soil stunted the trees and how the little trees were really old. There is truth to the story about slow growing trees. Many plants are not tolerant of the unique chemistry of serpentine soil, and the sluggish growth of tolerant species causes organic soil to accumulate slowly. In places, the soil is sufficiently thin and droughty that woody plants don’t grow at all. That is why it is called a serpentine barren. The good story blinded everyone to another one, an ecological story that will define Soldiers Delight in the 21st century.

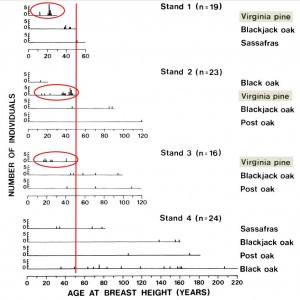

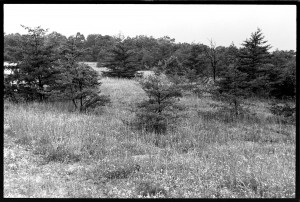

There was an alternate explanation for all of those small Virginia pines at Soldiers Delight. Instead of being stunted, they might have been small because they were young. Soldiers Delight was being invaded by a lovely, native pine tree, and nobody noticed. Throughout the 20th century, Virginia pines established in the grassy openings. They grew slowly, but new ones kept germinating. At mid century, the waving grasslands punctuated by scattered pines were the picturesque essence of Soldiers Delight. It was not until the 1980s that Robert Knox (1984) and Wayne Tyndall (1992) began to document and publish the new story; the pines were taking over the grasslands, filling in the savannas among widespread oaks, shading out the rare wildflowers, changing the landscape.

By this time Soldiers Delight was owned by the state, the Endangered Species Act was law, everybody loved Soldiers Delight’s rare flowers, and conservation was focused on protecting natural areas from change. So a change was made. In 1995, Maryland approved a plan to maintain the serpentine grasslands in their “pre-colonial” state. Since 1990, thousands of Virginia pines have been cut, and many dozens of acres have been burned. This appears to be working, although I haven’t seen results of post treatment monitoring or comparison with controls or with pre treatment conditions, which I assume are being done. Grasses tend to respond well to clearing and burning, but time will tell whether this new disturbance regime encourages the long term health of the grasses and herbs that managers want to preserve.

There are a few 18th century documents that mention the “Great Pennsylvania-Maryland Barrens” which were said to cover 100,000 acres, including 3,000 at Soldiers Delight. Nobody knows what this vegetation looked like or why it was not forest, but it apparently had little merchantable timber, and recent fire is the only reasonable explanation for the absence of thick forest on non-serpentine land. The historical reports are from the first Europeans to see the barren areas, after which the forest swallowed up any of this rich Piedmont land that was not converted to pioneer farms. There are a couple of one line anecdotes describing Native American burning of these areas in the early 1700s. So it is reasonable to hypothesize that people had a hand in creating the barrens observed by settlers. It seems likely that a series of large fires, wild or human-caused or both, preceded the first European observers. There is good indication that Soldiers Delight was not well forested in 1700 but it’s probably important to admit that we don’t know exactly what Soldiers Delight or other barren areas looked like then, and don’t really know what role Native Americans had played in altering the vegetation.

If Soldiers Delight had been cleared by pre-colonial fires, the unique soil properties would have greatly slowed the return to forest. A century of industrial chromium mining could have added to the delay. Maybe the invasion of Virginia pines in the 20th century was the expected trajectory at Soldiers Delight. Maybe the natural ecosystem that should dominate the 21st century is a burgeoning forest of scruffy oak and pine and sassafras, a unique ecosystem in the world. What got in the way of this natural succession are the environmental movement, our fascination with rarity, and the Endangered Species Act. We value what is in short supply, and several plants of the Soldiers Delight grassland are making their last stand in the state or in the world. Doing nothing at Soldiers Delight might be to watch the sandplain gerardia, fameflower, vanilla grass, and fringed gentian disappear. It might actually be illegal not to act.

So Soldiers Delight is now a garden. A fascinating, elaborate, expensive flower garden. It will be sad to go back there and see the current round of human interference with a system that was finally recovering from 19th century mining when I first saw it. I love gardens, and seeing those rare species again would be exciting, although I fear that I will not even be allowed off the trails to look for them. It would be a powerful experience to retrace my 40 year old steps and find where I took these old photos. A 40 year interval between landscape photos can reveal untold details of natural processes, but these repeats might show only what the chainsaw and torch have done.

The power of Soldiers Delight once came from the earth, from its oceanic heavy metal, from unfettered competition among plants, and from decades of human neglect. Of these, only the heavy metal remains. At least now we know where that came from.

I am young enough that I have no firsthand knowledge of the state of scientific thought on serpentinites in the 1950’s and 1960’s, but it’s been my understanding that Harry Hess at Princeton University was developing the ideas that led to the Seafloor Spreading Hypothesis as early as the mid-1950’s, though they didn’t see the light of publication until the early 1960’s. That he was pondering the origin of serpentinites as early as the mid-1950’s, however, is unquestionable in light of his 1955 publication of “Serpentines, orogeny and epeirogeny” (http://specialpapers.gsapubs.org/content/62/391.short) in A. W. Poldervaart’s “Crust of the Earth.” (GSA Special Paper #62).

I certainly think it’s fair to say our modern understanding of the origin of serpentinites was not widespread in the early 1960s, but I’m always a little hesitant to be too critical of the general state of geologic knowledge in times past.

Thanks Ron. It’s good to know that there was someone right up the road in Princeton who could have told us much more about Maryland serpentine. It must be fascinating to know the 20th century history of geology and understand how they dealt with the paradigm shift to plate tectonics. Hess was definitely well on his way in 1955: “Finally it is suggested that many features of suboceanic topography might be the result of uplift caused by serpentinization of peridotite below the Mohorovičić discontinuity [crust mantle boundary]…” He is still rather tentative, but it’s amazing that he had sort of figured out seafloor spreading five years before his hypothesis was presented in 1960. It’s also apparent that serpentinite was a crucial clue to discovering the driving force of all geology. Go serpentinite.

beautifully written

Wow, Thanks. It might be because the subject is something that once meant a lot to me, but which I have ignored for 30 years. Maybe I should write about ethical behavior next.