Click photos to enlarge.

Soldiers Delight would be a lot less interesting to some were it not for its contribution to the economic history of Baltimore County, Maryland. Serpentine outcrops including Soldiers Delight, Bare Hills, and the State Line Barrens in Pennsylvania supplied most of the world’s chromium ore in the mid 19th century. Issac Tyson, and later his sons, owned land and operated mines at these places, shipping all the chromite to Baltimore and monopolizing the industry from the 1820s until after the Civil War. But the long term impact of this activity may have been more ecological than economic.

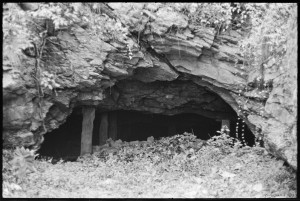

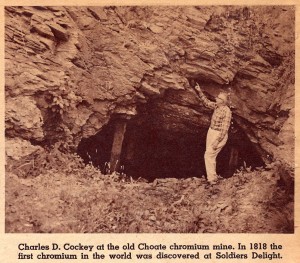

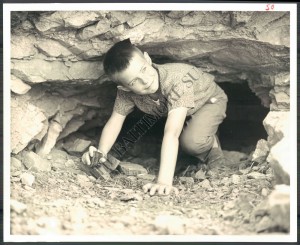

At Soldiers Delight there was placer mining of “sand chrome” along stream beds (e.g., the Triplett, Gore, and Dolfield Buddles) and also ore extraction via open pits and deep mine shafts. The Weir mine, north of Ward’s Chapel Road, had two vertical shafts as much as 250 feet deep with side drifts, and the Choate mine, east of Deer Park Road, had an angled shaft up to 200 feet long. The Harris mine, about a mile northwest of the Choate, had four shafts less than 100 feet deep. The Calhoun mine, two miles north of the Choate, had two shafts, one of which was about 100 feet deep. Two smaller mines were also present.

In the 1960s we bemoaned the environmental damage being done by the Baltimore Ramblers motorcycle club which allowed dirt bike riding on a large parcel of serpentine barrens they owned. But a century earlier, Soldiers Delight was an industrial mining district that must have been dramatically scarred by surface rock removal, excavated stream valleys, multiple mine shafts, tailings piles, loading docks, haul roads, processing plants, equipment dumps, offices, and employee housing. There is very little information about the effects of this activity, but dozens of people living and doing this kind of work on a fragile landscape at a time when wood fires were the primary means of heating and cooking suggests that the vegetation both in and around the mining area must have been dramatically altered.

Although the Choate mine was readied for operation again before it closed for good in 1918, and other sporadic mining activity lasted until 1925, most mining in Soldiers Delight had ended by 1880. So the 20th century was a time of recovery for Soldiers Delight vegetation. Serpentine tolerant prairie grasses established on disturbed sites, as they are returning today on the old Baltimore Ramblers property. Trees in the oak forests grew large again after a century of intense harvest, and Virginia pines began to spread across the grasslands. By 1950, Soldiers Delight seemed both wilder and more natural than the surrounding landscape where continuing disturbance by agriculture, logging, or suburban sprawl kept a domesticated ecosystem in a state of early succession and laced with introduced species.

In fact, Soldiers Delight had wild beauty in 1960 mostly because it was uninhabited and neglected, and because serpentine soil made it resistant to invasion by exotic weeds. And the serpentine barrens were grassland, a rare and therefore valued habitat in the forested east. This was a unique and fascinating place, and a place worth saving. But in the 1960s, it was moving fast on a successional trajectory away from industrial disturbance. We liked what we saw then, and decided we wanted to keep it just the way we found it. That decision may have suffered from a lack of both hindsight and foresight.

The history of mining at Soldiers Delight connects people to the landscape, and is appropriately highlighted in current interpretive material. But that history may explain much more about the Soldiers Delight landscape than we realized in the 1960s or have accepted today. It may have largely determined the nature of the plant communities that made so many people work so hard to protect them from change without recognizing that the very nature of those communities was change.

Without today’s management plan, some rare species might disappear, but Soldiers Delight would be developing toward a more natural state instead of being nudged awkwardly into the recent past. The attempt to revive some rare species by reversing woody plant succession on hundreds of acres is a grand experiment. The resulting landscape will be largely artificial, so I hope it encourages a few desired species. And I hope some control areas remain so we can eventually learn what a mature serpentine community really looks like at this place.

Is the mine entrance still accessible? I’m guessing the mine itself is not.

I think the Choate mine entrance is still open but a sturdy security fence surrounds the area.

lol, just hop it.

https://www.mininghistoryassociation.org/Journal/MHJ-v24-2017-Johnsson.pdf

Chris – Thought you might enjoy this article about the history of the Choate Mine I published in the Mining History Journal in 2017. I am a volunteer ranger at Soldiers Delight, lead mining history hikes 2X per year, have adopted the Choate Mine Trail, and built the fence around the mine. Johnny Johnsson-Mining Historian

‘The Triplett Buddle’ would make a great name for a rock band.

Guitar, bass, drums, and on vocals, Placer Domingo?