Some “then and now” sliders in the last post about Glacier Bay suggested that blueberry and hemlock were spreading in the understory at two of the older study sites we visited last month. Below I am trying out another method of displaying these pairs of old (1990 or 1995) and new (last month) photos. Some new photo pairs from York Creek and Beartrack Cove have been added as well as pairs from a third site.

Above: Three photo pairs from York Creek (Site 8, ice-free about 1825). Each pair includes an early photo from a Kodachrome slide (June 1990 or 1995, smaller image) and a June 2021 version of the same scene. Each pair suggests that both blueberry and hemlock have become more important in the understory.

Above: Two photo pairs from Beartrack Cove (Site 9, ice-free about 1835).

Each pair includes an early photo from a Kodachrome slide (June 1990, smaller image) and a June 2021 version of the same scene. Each pair suggests that both blueberry and hemlock have become more important in the understory.

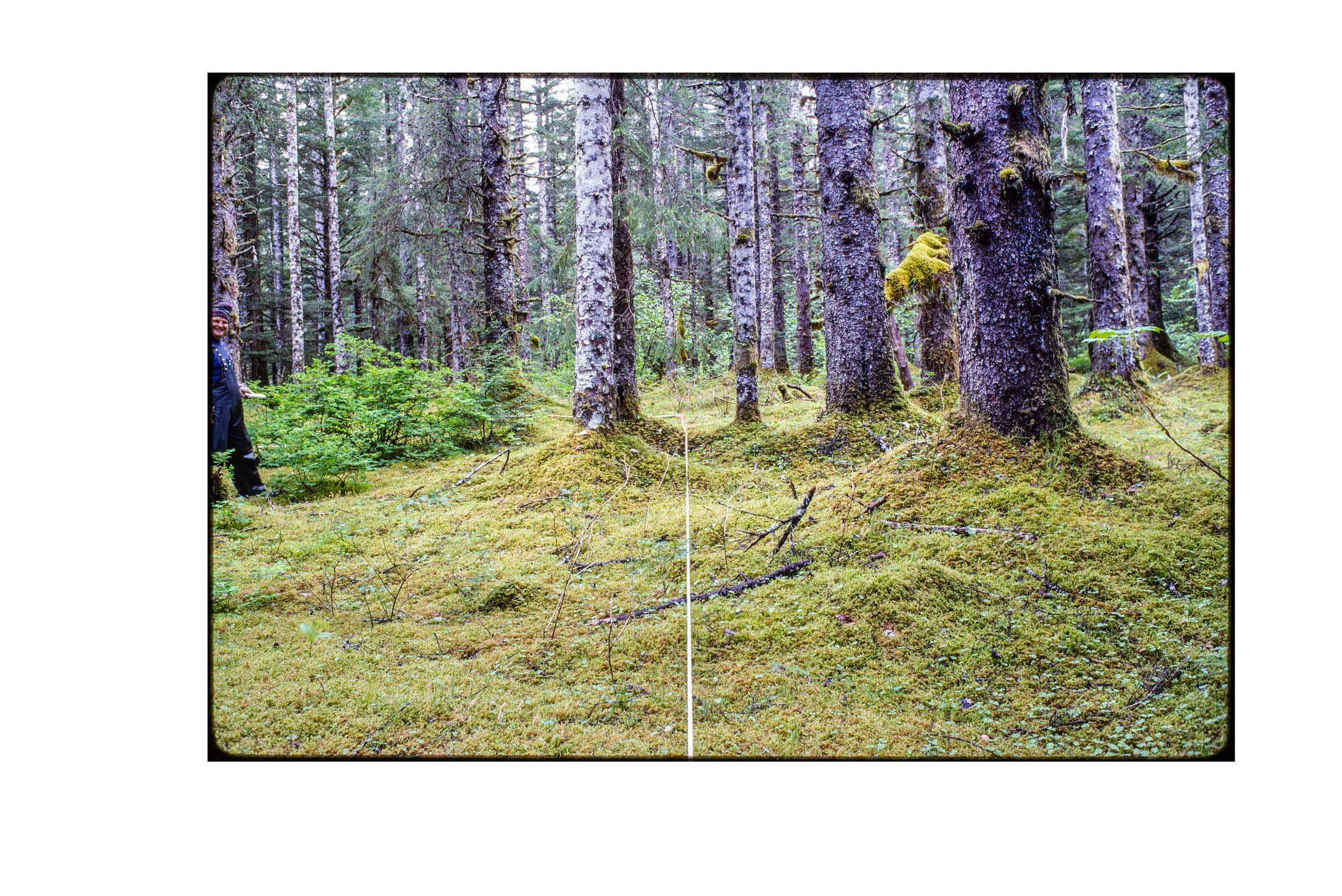

I also put together some new photo comparisons from Bartlett Lake, the oldest site (about 55 years older than York Creek or Beartrack Cove). These suggest that blueberry there was already widespread in 1995. It looks like blueberry has continued to spread, but unlike the York Creek and Beartrack Cove sites there is no indication that hemlock has become more important during the last three decades.

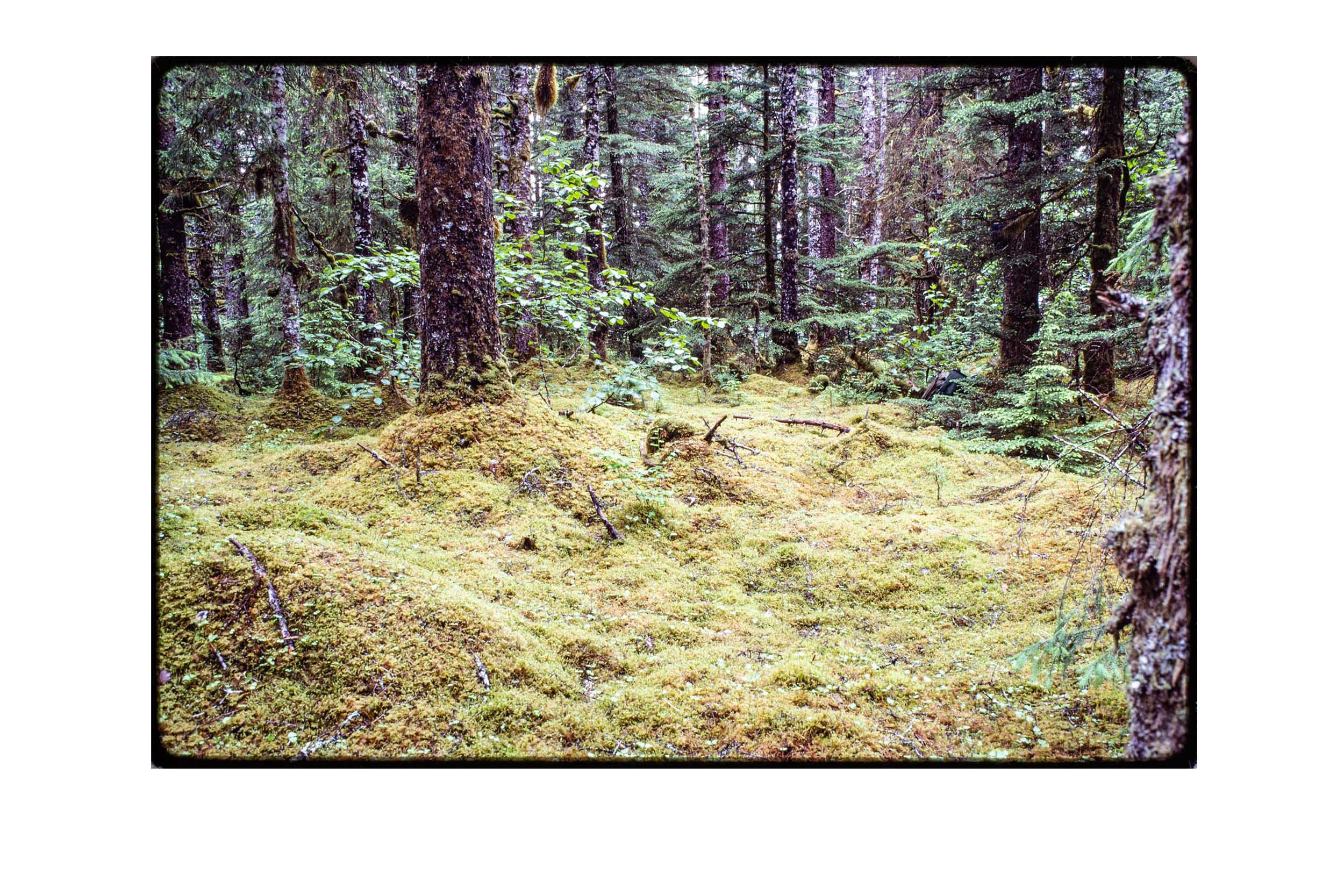

Above: Three photo pairs from Bartlett Lake (Site 10, ice-free about 1770).

Each pair includes an early photo from a Kodachrome slide (June 1995, smaller image) and a June 2021 version of the same scene. Each pair suggests that blueberry was abundant 30 years ago and has increased some since then. Hemlock has not become conspicuously more important in the understory.

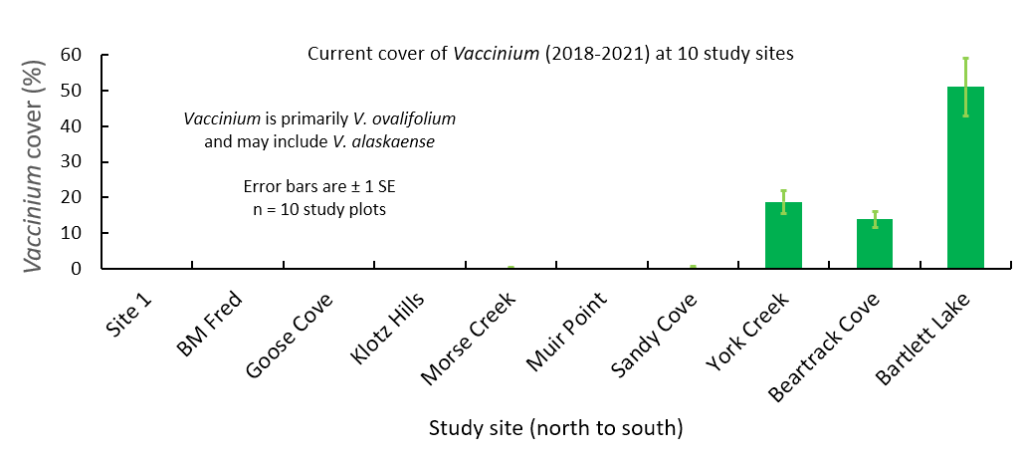

There is no need to speculate further about the existence or magnitude of these understory changes. The data I brought home include estimates for the percent cover of blueberry in each study plot and also the number of western hemlock seedlings, saplings, and trees in each plot. We also have these same data from all 10 of the study sites along the eastern shore of Glacier Bay.

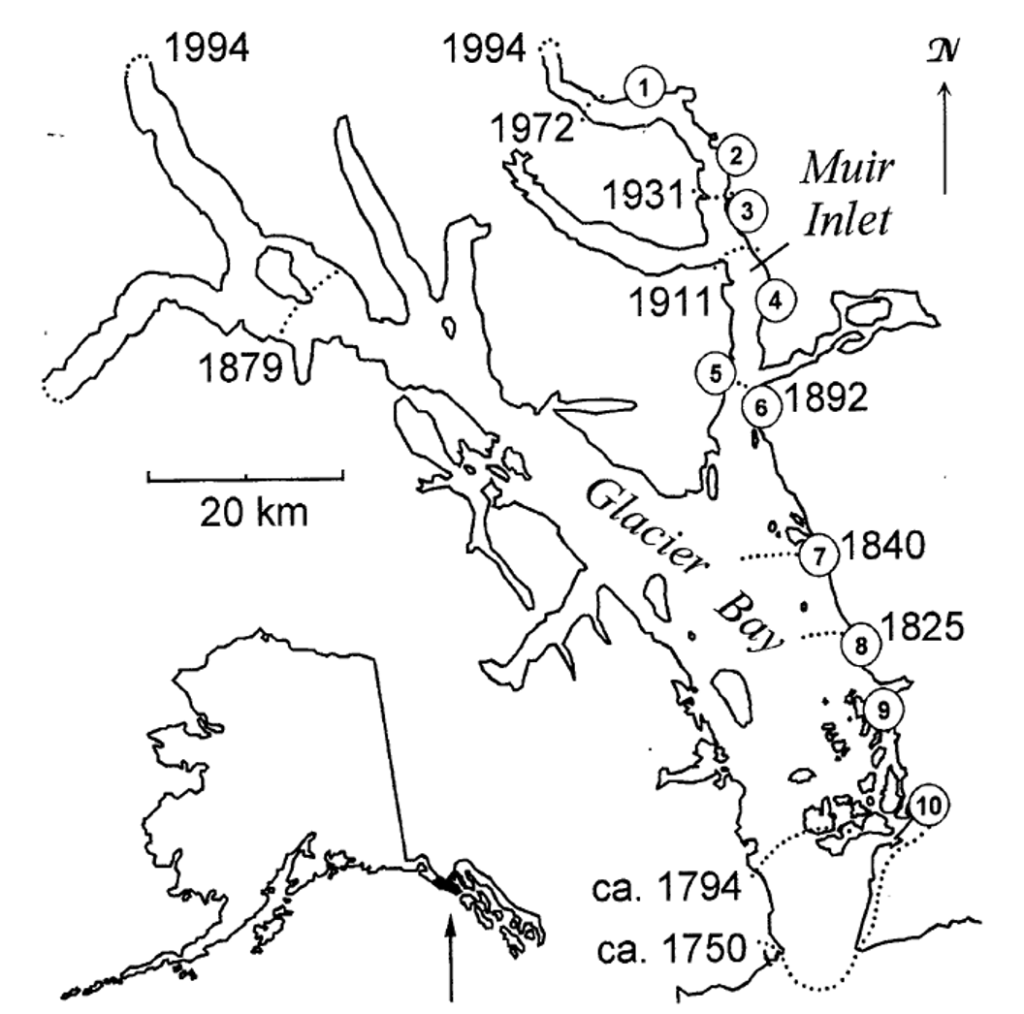

The story of both blueberries and hemlock is a story about the three oldest sites. Blueberry shrubs are common at Sites 8, 9, and 10 (York Creek, Beartrack Cove, Bartlett Lake) and rare at younger sites (Figure 1). One or two blueberry plants are present in two or three plots at Morse Creek and Sandy Cove but absent at the other sites.

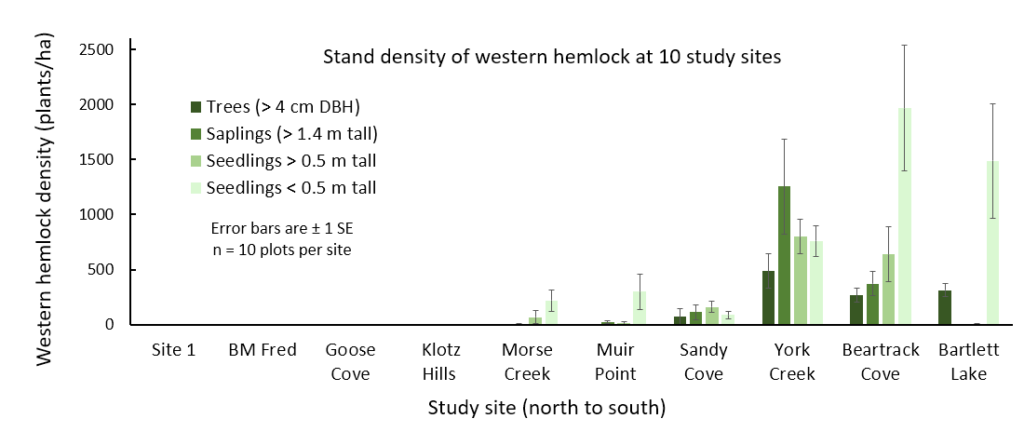

Western hemlock trees were absent at all sites younger than York Creek when the study plots were established (1988-1990) although a few seedlings and saplings were present at three younger sites (Fastie 1995 Table 4). Today, hemlock trees (DBH > 4 cm) are common only at the three oldest sites and present only at one additional site (Sandy Cove, Figure 2).

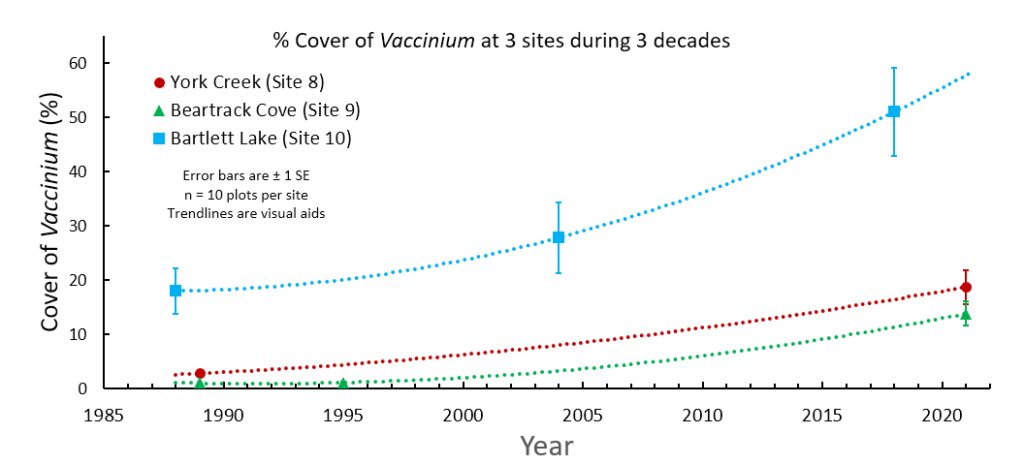

Data about blueberry and hemlock in each study plot have been collected three or four times in the last three decades. So we can determine the reliability of the three decades of photographic evidence of their spread through the understory at the three oldest sites. The measured percent cover of blueberry has increased several fold at each of these sites (Figure 3). Three decades ago the oldest site (Bartlett Lake) had about as much blueberry as the two younger sites have today (Figure 3). This pattern is evident in the repeat photos.

The York Creek and Beartrack Cove sites are similar in age and are about 55 years younger than Bartlett Lake. The greater blueberry cover at Bartlett Lake is likely due to that site’s greater age and probably hints at the future for the two younger sites. In other words we can use these three sites as a chronosequence and predict the future of younger sites based on the current state of an older site. Or we can know the history of the oldest site by looking at the series of younger sites.

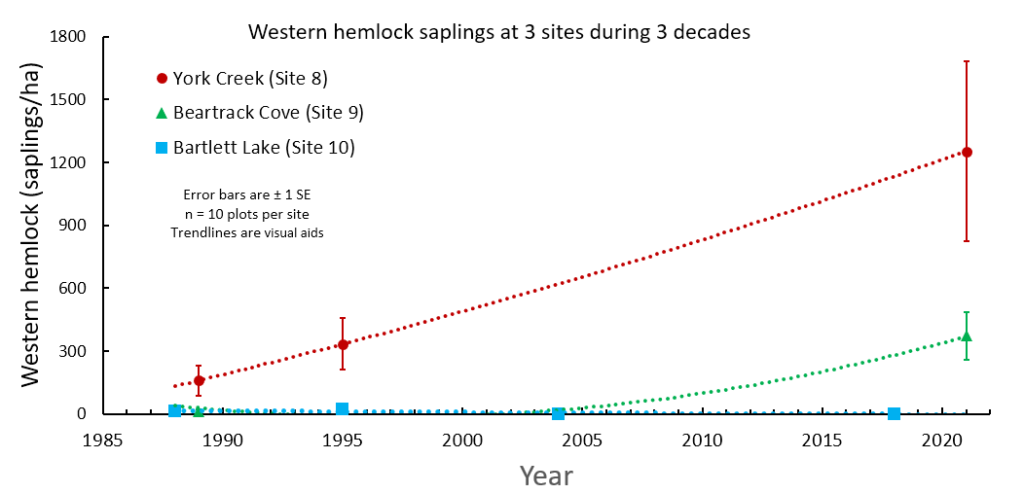

The history of western hemlock differs from that of Vaccinium at the three oldest sites. As the repeat photos at York Creek and Beartrack Cove suggest, there are more hemlock saplings now than there were 30 years ago (Figure 4). But York Creek, not Bartlett Lake, is the hemlock regeneration champ. Bartlett Lake has lots of little hemlock seedlings and old trees, but nothing in between (Figure 2). Apparently the old trees produce seeds, then seedlings establish, but few if any seedlings survive to become saplings.

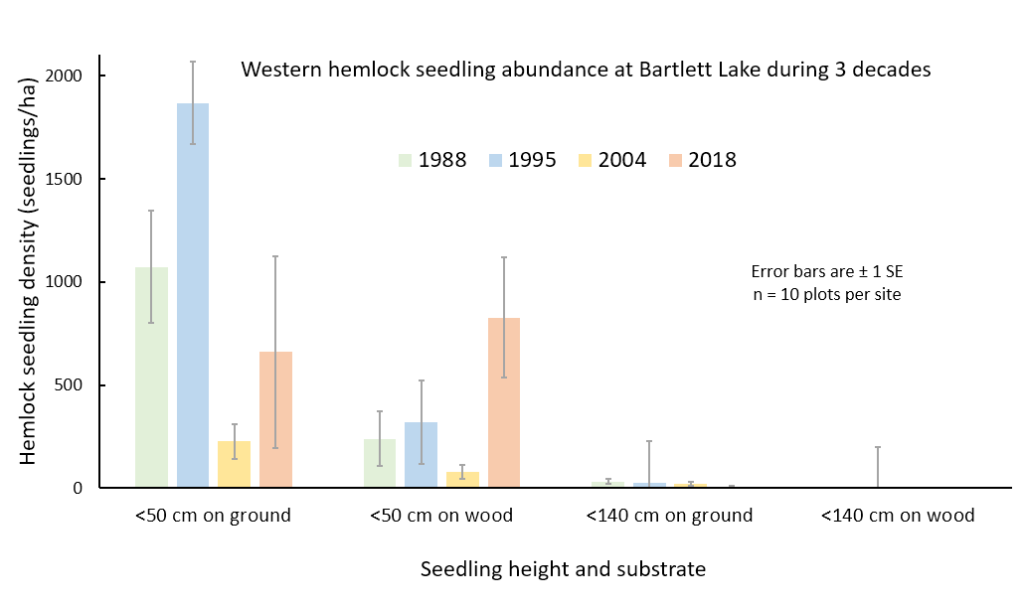

The poor success of hemlock regeneration at Bartlett Lake is conspicuous in the detailed seedling results (Figure 5). Almost all of the hemlock seedlings are small (< 50 cm tall) and this has been true for 30 years (Figure 5). In other words there are always small hemlock seedlings but few of them have survived to become taller than 50 cm.

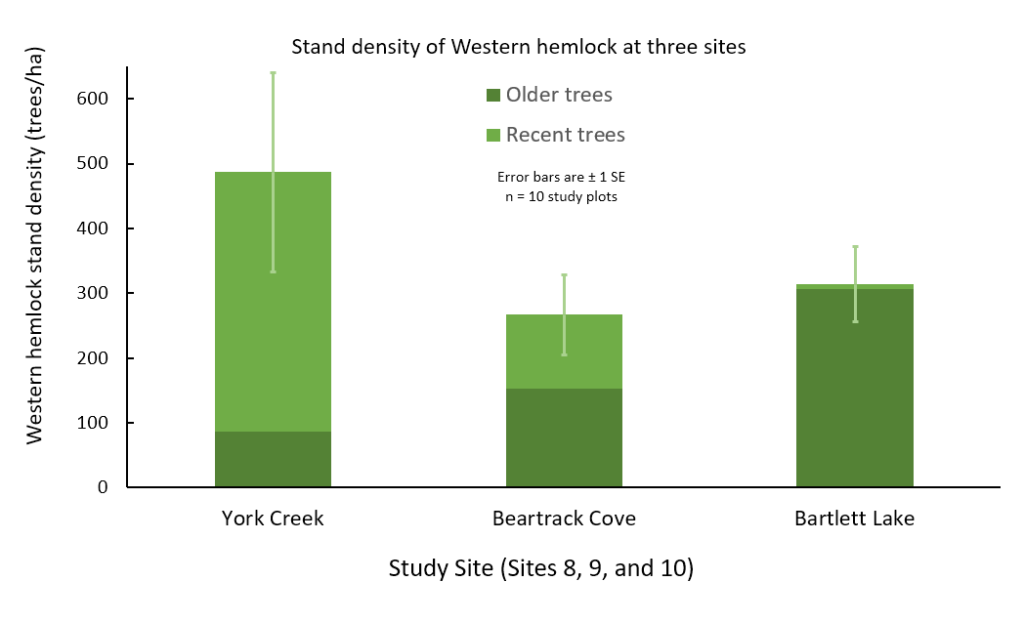

There are lots of big hemlock trees at Bartlett Lake and when the study began the site had more hemlock trees than any other site. Today, York Creek has the most hemlock trees, although most of them have just recently grown from sapling size to tree size (DBH > 4 cm). In contrast, almost no new hemlock trees have been added recently at Bartlett Lake (Figure 6). I do not have an explanation for the failure of hemlock at Bartlett Lake to reproduce while healthy saplings and small hemlock trees are common at the two younger sites.

The dark green bars in Figure 6 are a good approximation of the hemlock stand density in 1990 at these sites (Fastie 1995, Table 4). In 1990, most of these trees were understory or subcanopy trees and a few of these are now part of the overstory. The light green bars suggest that a second cohort of hemlock could become an important part of the understory (and maybe the future overstory) at York Creek and Beartrack Cove. There is no sign of a coming second cohort of hemlock at Bartlett Lake and also no indication that there was ever a second cohort there (Fastie 1995, Fig. 4).

It does not appear that using these three old sites as a chronosequence would lead to reliable conclusions about the stand dynamics of western hemlock. The current state of the oldest site (Bartlett Lake) does not allow us to predict the future of hemlock at York Creek or Beartrack Cove.

I have characterized these three old sites as being similar because of the stand dynamics of Sitka spruce and their inferred early site histories. It appears that the recent dynamics of hemlock might make these sites less similar than I thought.

In relation to all 10 study sites on the east side of Glacier Bay, these three old sites are more similar to each other than to any other site. Sites 8-10 differ from Sites 2-7 because 8-10 lack evidence for early alder dominance, and Sites 8-10 differ from Sites 1-4 because 8-10 lack evidence for early importance of black cottonwood (Fastie 1995). Although Sites 8-10 are following the same no-alder, no-cottonwood pathway, they now might be developing important differences in the dynamics of the overstory dominants spruce and hemlock.

Instead of leading to a divergence of these forest communities, these differences might be adjustments that eventually make these communities more similar to one another. For the next century or two, it is likely that all three sites will support forests with both Sitka spruce and western hemlock in the overstory and lots of blueberry spreading over the forest floor.

Hi Chris,

Hope you’re doing well. I wrote Brian Buma for a reprint (I don’t know him — you probably do) and he mentioned that you lived not too far from me (Exeter NH for me), so I found your blog. I’m jealous of you getting back to Glacier Bay for some work — I would love to do that and do some follow-up fungal and isotope work — hopefully someday! I’m still in touch with Erik Lilleskov — I think you knew him from Alaska?

You can reach me at unh.edu.

Cheers,

Erik