In 2012 I tried top grafting, which requires that both the scion plant and rootstock plant be cut clean off and stuck together. They are held in place with a little clip and kept in the dark for several days. I learned how to do this from this video. I think I waited too long and the plants were too big when I grafted them. They all died. Some of the discarded scion stubs, cut off an inch above their peat pots, started to sprout, so I at least salvaged something from those 40 plants I grew from seed.

This year I grew another 40 plants for grafting, half Emperador rootstock plants and half various varieties that I was also starting for normal growing. But this time I tried side grafting in which the scion is not lopped off completely at first. Only the rootstock is chopped off and a wedge tip is inserted into a slice into the scion stem. This worked much better and almost all of them survived. Unfortunately, I was in a hurry early one morning to finally sever the scions from their own roots. I carefully identified which root was the scion, and then groggily SLICED THROUGH THE ROOTSTOCK. I ruined several successful grafts before I woke up. Add that loss to several that died because the graft is weak and will break if the plant falls over or blows in the wind, and I ended up with only about six grafted plants established in the garden. That is an improvement over last year, and maybe enough to encourage another try next spring.

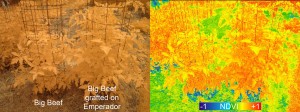

I used my Public Lab infrared camera to make NDVI (normalized difference vegetation index) images of my side by side plantings in an attempt to identify higher productivity, but the real success of the grafted plants has to be measured in fruit production. Even the size of the plants was not a good index of success because the grafted plants had been started two weeks ahead of the others, and that advantage was not all lost in the grafting process. I think most of the grafted plants produced more fruits, but that is very hard to judge without counting or weighing every tomato harvested, which is never going to happen in my garden.

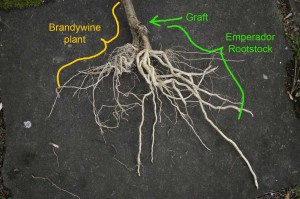

The best indication of the superiority of grafted plants was apparent when I yanked up the roots in the fall. Grafted plants had substantially larger root systems. But the best measure is from one grafted Brandywine plant that was intentionally allowed to keep both of its roots. I never severed the scion’s root, so it grew all summer with its own root and also an Emperador root.

The trick to top grafting is to do it when the plants are very young. Use the silicone tubes. Older plants try the wedge technique. http://Www.patchofdirtonline.com for my article on grafting

Wouldn’t keeping the scion roots expose the plant to diseases that the rootstock is resistant to? That is for example, fusarium wilt would be given the normal easy path to infect the plant.

Hi Mark,

I think you are right. Verticillium and Fusarium wilts enter the plant through the root. I don’t know whether my particular root stock was resistant to those or other diseases or whether it was just a more vigorous strain. Either way, the rootstock is likely to be better protection from those fungi. It seems that those and other wilts are so abundant in my soil that the tomato plants always suffer from them. The grafted plants were bigger, but they also slowly declined as the leaves wilted from the bottom of the plant. There are some rootstocks that have shown resistance to Fusarium and Verticillium, so I should probably try those. The seeds are really expensive though.

Chris